Most strategy reviews are theater. Executives sit through slide decks. They nod at familiar metrics. Then they leave the room and keep doing exactly what they were doing before.

The problem is the process: Strategy reviews fail when they confuse reporting with deciding, when they prioritize looking rigorous over being useful. A real strategy review doesn't summarize the past but shapes the future by forcing hard choices about where to play and how to win.

This guide shows you how to design and execute strategy reviews that actually move the needle. You'll learn what separates a strategic review from a business review, how to structure the review process so leadership engages deeply, and how to use a four-step decision checklist that turns evaluation into action.

You'll see how companies like Microsoft, Unilever, and Siemens run these sessions as decision engines rather than compliance exercises. And you'll understand when to schedule reviews based on your business context - because timing matters as much as process.

What a strategy review actually is and what it is not

A strategy review is a structured process for evaluating whether your current business strategy still makes sense given new information. It assesses

- whether your strategic objectives remain valid,

- whether your assumptions hold, and

- whether your resource allocation matches your stated priorities.

It is not a quarterly business review. It is not a budget defense. It is not a performance review dressed up with strategy language.

But the distinction matters:

- Performance reviews track execution against the plan. They measure key performance indicators like revenue, pipeline velocity, and headcount utilization.

- Strategy reviews question the plan itself. They ask: Should we still be pursuing this objective? Has the competitive landscape shifted enough to invalidate our thesis? Are we funding yesterday's priorities while underfunding tomorrow's growth opportunities?

Too many organizations conflate the two. They calendar quarterly strategy sessions but fill them with operational metrics. These numbers matter for assessing progress on day to day operations. They rarely illuminate strategic choice.

A genuine strategic review confronts three questions:

- Do our strategic goals still align with market reality and organizational capability?

- What evidence would cause us to change course?

- What are we deciding today, and who owns execution?

From goals and objectives to strategic objectives that matter

Strategic objectives are specific choices about where you will compete, how you will win, and what you will stop doing to make that possible. Thus, the difference between goals and objectives and true strategic objectives is testability.

A goal says, "become a leader in sustainable materials." A strategic objective says "capture 30% share of the bio-based polymer market in automotive applications by 2027 through exclusive partnerships with three tier-one suppliers."

Effective strategy reviews demand this precision because vague objectives can't be validated against reality. You can't assess progress if you haven't defined what progress looks like. You can't identify gaps between the current strategy and desired outcomes if the outcomes remain fuzzy.

The best strategic objectives share three characteristics:

- They specify a measurable outcome tied to competitive advantage.

- They define a time horizon that aligns with your planning cycle.

- They force resource allocation decisions by implying what you won't do.

Who participates and what they prepare beforehand

Strategy reviews fail when the wrong people participate or the right people show up unprepared. The composition of your review session determines whether you get rubber-stamping or rigorous debate.

Start with decision makers. These are the business leaders and department heads who control resource allocation. They need sufficient context to challenge assumptions and sufficient authority to commit to strategic changes.

Add key stakeholders who inform strategic decisions without making them. In R&D and innovation contexts, this often includes technical fellows who understand feasibility, business development leaders who see market trends, and finance partners who model scenarios. These voices provide necessary perspectives without diluting decision rights

Limit the room. The management team or leadership team shouldn't attend en masse: Fifteen people debating leads to compromise, not clarity. Thus, six to eight is optimal.

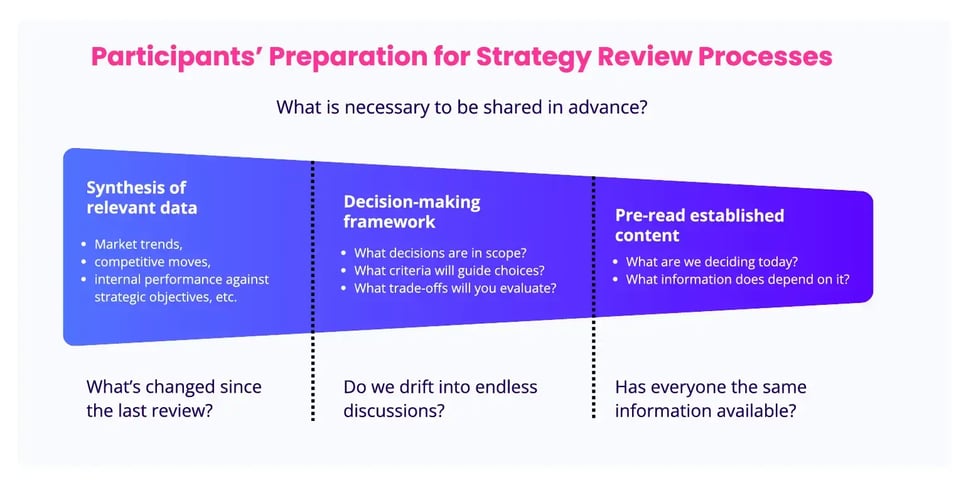

Now address preparation: As the best strategy reviews happen before the meeting, participants should receive three things at least one week in advance (Exhibit 1).

Exhibit 1: Three necessary steps for the participants' preparation for a strategy review process

Teams that skip pre-work end up spending the first hour of the review getting everyone on the same page. That's an hour you can't spend making decisions. But with the right participants prepared properly, you can focus on designing a review process that drives real outcomes.

Designing a review process that leaders take seriously

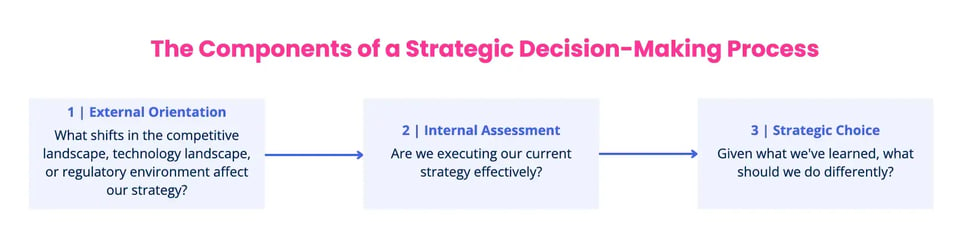

A credible strategy review process balances rigor with pragmatism. It needs enough structure to force critical thinking and enough flexibility to adapt to the business context (Exhibit 2).

Start by defining the evaluation process itself: What questions will you answer? In what order? With what information? The sequence matters. If you start with budget discussions, you are biased toward incremental thinking. If you start with "what's changed in our environment," you open space for strategic changes.

Exhibit 2: The strategy review process

This flow prevents a common failure mode as many teams jump straight to "what should we do" without establishing why anything should change. The result is a random walk strategy, new priorities emerging from whoever argued most forcefully rather than from data driven decision making.

Effective strategy reviews also separate evaluation from decision. Spend the first portion of your session diagnosing: What's working? What's not? What's changed? Resist the urge to solve problems as they surface. Once you've built a complete picture, then shift to decisions.

The timeline matters too. Don't try to run a comprehensive strategic review in two hours. You'll either rush through critical analysis or skip decisions entirely. Block four to six hours minimum. If that feels impossible, your strategy is too complex, or your objectives aren't clear enough.

Document everything. Not as theater, but as institutional memory. What did you decide? What assumptions are you making? What would cause you to revisit this decision? Future reviews depend on understanding what you committed to and why.

Build in accountability mechanisms. Who owns each decision? What's the deadline? How will you track progress? Strategy reviews that end without an action plan are just expensive conversations.

The review process itself is only as good as the inputs feeding it. Let's examine how to gather and evaluate the right information.

How often to run strategy reviews and when to trigger them

Annual strategy reviews made sense when markets moved slowly. In R&D and innovation contexts, waiting twelve months between evaluations guarantees you're funding obsolete bets.

Most innovation organizations benefit from a dual-rhythm approach: Run comprehensive strategy reviews twice per year, aligned with fiscal planning cycles. These sessions validate objectives, test assumptions, and make major resource allocation decisions. Between these, run lighter quarterly check-ins that track progress and address emerging issues without reiterating the entire strategy.

Adjust frequency based on portfolio maturity. Early-stage initiatives need quarterly evaluation due to high uncertainty. Mature programs can extend to semi-annual or annual reviews.

Trigger ad-hoc reviews when the landscape shifts materially: major competitive moves, regulatory changes, technology breakthroughs, M&A activity, or leadership transitions. The test isn't "something happened" but "something happened that questions whether our strategy still makes sense."

Thus, match your cadence to your planning cycle and rate of environmental change. If you're mostly rehashing the same discussions, you're reviewing too often. If major assumptions broke months ago without detection, you're reviewing too infrequently.

Gathering and evaluating the right input

Strategic decisions require different inputs than operational reviews:

- You need signals about the future direction of your markets, not just reports on past performance.

- You need insights about what might happen, not just data about what did happen.

The challenge is separating signal from noise, as every stakeholder brings relevant data. And not all of it matters strategically.

Turning raw data into strategic insights

Data collection is necessary but insufficient, as the value lies in data analysis that extracts meaning for decision makers. Therefore, it is necessary to distinguish between performance metrics and strategic indicators.

Performance metrics tell you how well you're executing: development cycle times, success rates, and cost per experiment.

Strategic indicators tell you whether your strategy still makes sense: shifts in customer needs, emerging technologies that could disrupt your roadmap, competitor moves that change the game.

Both matter, and they answer different questions.

The best data-driven decision-making combines multiple sources:

- Quantitative data provides rigor.

- Market data shows trends.

- Internal data reveals capability gaps.

But numbers alone miss context: A declining market share number might indicate strategic failure, or it might reflect a deliberate choice to focus on more profitable segments.

This is where qualitative insight adds depth. To these count customer interviews, technical assessments, or competitive intelligence. The goal is not to collect data, but to gather it systematically around the questions a review must answer.

A golden rule of thumb is to be ruthless about filtering: If a data point doesn't inform a decision in scope, exclude it. Progress reports on initiatives you're not reconsidering don't belong in a strategy revies and they can be saved for operational reviews.

When focus groups add value and when they distort signal

Focus groups are a double-edged tool in strategy reviews: Used well, they provide valuable insights about customer needs, user behavior, and market perception. Used poorly, they create false confidence in ideas that won't scale.

- They're important when you need to explore ambiguity. Early-stage innovation work often involves problems customers can't articulate clearly. A well-designed focus group helps you understand both the job to be done and the feature requested.

- They're useful for testing messaging and positioning. If you're considering entering a new market, focus groups can reveal how potential customers perceive your brand and whether your value proposition resonates.

- They work on identifying weak signals that quantitative data misses. A dozen conversations might surface an emerging need that won't show up in market data for another year.

But focus groups distort the signal in predictable ways: Participants tell you what they think you want to hear.

- Vocal participants dominate quieter ones.

- Group dynamics create false consensus.

- Skilled moderators mitigate these effects but can't eliminate them.

What is even worse is that focus groups can't predict behavior. People are terrible at forecasting their future choices. Asking "Would you buy this?" yields unreliable answers. Observing what people actually do beats asking what they'd hypothetically do.

Separating performance discussion from strategic choice

This is where most strategy reviews fail because they blend performance evaluation with strategic evaluation until neither gets proper attention. What performance discussion really asks: Are we executing our current strategy effectively? Are key performance indicators trending in the right direction? Where are we behind the plan and why?

Instead, strategic choice asks: Is this still the right strategy? Should we double down, pivot, or exit? What new initiatives should we start? What existing programs should we stop?

These are different conversations requiring different mindsets. Performance discussion is diagnostic: It's about problem-solving and course correction within an established framework. Strategic choice is generative: It's about questioning the framework itself.

When you mix them, people optimize locally rather than thinking systemically.

- They defend their performance rather than questioning whether they're solving the right problem.

- They explain variance to plan rather than asking whether the plan still makes sense.

Separate them explicitly in your agenda.

- Run performance discussions first if you must include them, but time-box them aggressively.

- Make it clear when you're shifting modes: "We've reviewed our execution. Now let's evaluate whether we're executing the right strategy."

Better yet, handle performance reviews in separate forums, as your strategy review should assume everyone has seen the performance data and focus entirely on strategic choice. This keeps the conversation at the right altitude.

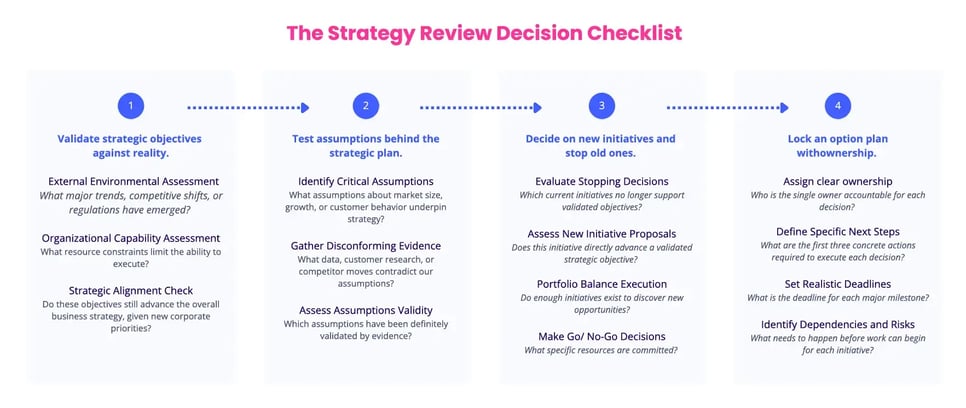

The strategy review decision checklist leaders actually need

Decision frameworks fail when they're too abstract or too rigid. Therefore, the checklist below provides structure without constraining judgment. It forces the critical thinking that separates real strategy reviews from performative ones (Exhibit 3).

Exhibit 3: The strategy review decision checklist

This isn't a linear sequence, and you'll loop back as new information surfaces. But working through these four steps systematically ensures you make strategic decisions based on evidence rather than momentum.

Checklist step 1: Validate strategic objectives against reality

Start by testing whether your strategic objectives still align with the world as it actually is, not as you hoped it would be.

External Environmental Assessment

What major trends, competitive shifts, or regulatory changes have emerged since the last review? How do these changes affect our ability to achieve current strategic objectives?

Constantly shifting landscapes

The landscape shifts constantly: New competitors emerge. Technologies mature faster or slower than expected. Regulatory environments tighten or loosen.

If the external environment hasn't shifted materially, your objectives probably remain sound. If it has, assess whether your objectives are still achievable and still worth pursuing.

More forward-looking questions

- What future market shifts would invalidate these objectives entirely? This forces you to identify the conditions under which your strategy breaks.

- If three competitors consolidate and achieve scale you can't match, does your objective still make sense? If regulatory changes eliminate your core value proposition, what then? Knowing your strategy's breaking points prevents you from riding a dead horse.

Organizational Capability Assessment

What resource constraints or capability gaps limit your ability to execute these objectives? Is organizational focus sufficient, or are resources fragmented across competing priorities?

Failure of strategic objectives

Many strategic objectives fail not because they're wrong but because they're unrealistic. If you'd need to triple your R&D budget or acquire capabilities you can't build, the objective needs revision.

Questions to ask yourself

What capabilities must we build or acquire for these objectives to remain viable?

This surfaces the capability investments your strategy actually requires: If your objective demands real-time data infrastructure but your systems batch-process overnight, you've identified a fundamental gap that must be closed.

Strategic Alignment Check

Do these objectives still advance the overall business strategy, given new corporate priorities? Have any objectives become less relevant or misaligned with the company's direction?

Time to evolve objectives

Organizations evolve: A strategic objective that made sense two years ago might now conflict with new priorities.

If you're pursuing objectives that pull in different directions, you'll dilute effort without gaining a competitive advantage.

Questions to test objectives

What corporate-level changes would require us to stop pursuing these objectives?

If the company pivots from enterprise to SMB, if new leadership shifts from growth to profitability, if M&A changes your market position - any of these might invalidate objectives that were once sound.

Build this awareness upfront rather than discovering it after wasting resources.

The ultimate test

If we were starting from scratch today, would we choose this objective?

If the answer is no, you've identified a candidate for elimination.

Checklist step 2: Test assumptions behind the strategic plan

Every strategic plan rests on assumptions regarding market size, customer behavior, technology readiness, competitive response, or regulatory environment. The question is whether those assumptions still hold.

Identify Critical Assumptions

What assumptions about market size, growth, or customer behavior underpin this strategy? What technology readiness or competitive response assumptions drive the timeline? Write them down. A vague understanding doesn't survive scrutiny.

Questions to separate assumptions

Which assumptions, if proven wrong, would fundamentally break this strategy?

This separates nice-to-have assumptions from load-bearing ones.

-

If you're wrong about market size, you might capture a smaller opportunity.

-

If you're wrong about customer willingness to switch from incumbents, your entire strategy collapses.

Know the difference.

Gather Disconfirming Evidence

What data, customer research, or competitor moves contradict our core assumptions? Where are we seeing weak signals that challenge our strategic thesis?

Questions to dis-/ prove critical assumptions

What evidence would definitively prove or disprove each critical assumption?

This forces specificity. "We'll know customers want this if we see X metric move Y direction by Z date."

Build experiments to generate that evidence rather than waiting for market feedback after you've committed resources.

Assess Assumption Validity

Identify which assumptions have been validated or invalidated by evidence since the last review. This is where brutal honesty matters. Executives often cling to assumptions because changing them requires changing strategy. But proceeding on false assumptions guarantees failure.

Questions for still holding assumptions

Which critical assumptions remain untested and require validation experiments? What's our plan to test untested assumptions before committing more resources?

Some assumptions can't be fully tested. Make them explicit anyway. Knowing you're making a bet beats pretending you have certainty.

Monitoring for follow-up action plan

Which assumptions could break in the next 12 months? What early warning signals would indicate they're breaking?

This transforms assumption testing from a one-time exercise into continuous strategic intelligence.

Checklist step 3: Decide on new initiatives and stop old ones

This is the moment that separates real strategy reviews from theater. You must make actual decisions about resource allocation.

Evaluate Stopping Decisions

Which current initiatives no longer support validated objectives or are based on invalidated assumptions? What initiatives consume disproportionate resources relative to their strategic value?

Simple test to be applied

If this initiative didn't exist, would we launch it today knowing what we know now? If not, put it on the stop list.

Then ask: What's the actual cost of continuing versus stopping each questionable initiative?

This makes the trade-off explicit: Continuing a zombie initiative doesn't just waste its direct costs but it consumes leadership attention, creates organizational confusion, and blocks resources that could fund better bets.

Assess New Initiative Proposals

Does this initiative directly advance a validated objective with measurable outcomes? If it doesn't, it's not strategic, no matter how attractive it looks. What unique strategic capabilities does this initiative build? If it's just catching up to competitors rather than building differentiation, be clear about that.

The kill-criteria question

What evidence would prove this initiative is failing within the first 90 days?

This forces you to define success upfront and establish early tripwires. If you can't articulate what failure looks like, you can't manage the initiative effectively.

Evaluation of feasibility

Can you execute this with the available resources? Do you have the necessary capabilities or a credible plan to acquire them?

Estimate impact with specificity: What outcomes do you expect and over what timeframe? Fuzzy promises of "significant benefits" don't cut it. Quantify when possible. When you can't quantify, be explicit about what success looks like.

Portfolio Balance Check

Do enough exploratory initiatives exist to discover new opportunities versus exploit current ones? Does the portfolio balance short-term wins, long-term positioning, and defensive versus offensive moves? Are you over-indexed on short-term wins at the expense of long-term positioning?

The critical question

What percentage of resources should shift from current to new initiatives based on stopping decisions?

This connects stopping decisions to starting decisions. If you kill three initiatives consuming 30% of R&D resources, how should those resources be reallocated? Make the reallocation explicit.

Make Go/No-Go Decisions

Make yes/no decisions. Maybe means no. Pilot testing means maybe. If something is worth doing, commit resources. If it's not, kill it.

Questions for go-decisions

What specific resources (budget, headcount, leadership attention) are committed to each initiative? What conditions or kill criteria would trigger a decision to stop this initiative? Who has authority to pull the plug if kill criteria are met without requiring escalation?

The critical question

Who has authority to pull the plug if kill criteria are met without requiring escalation?

This last question is critical: If stopping a failing initiative requires the same approval process as starting it, you've created bureaucratic inertia that keeps bad bets alive too long. Delegate stop authority to the initiative owner with clear criteria.

Checklist step 4: Lock an action plan with ownership

Lock in the who, what, and when before leaving the room. Decisions without execution plans are only wishes.

Assign Clear Ownership

Who is the single owner accountable for each decision with the authority to execute? What decision rights does the owner have versus what requires approval or escalation?

Explicit authority boundaries

If the owner can make technical decisions but needs approval for budget changes over $50K, say so. Ambiguous authority creates constant escalation and slows execution.

Establish stop authority

Who has the authority to stop this initiative if the kill criteria are met?

Often, this should be the same person who owns execution. If they see the initiative failing against agreed criteria, they should be empowered to pull the plug without requiring the same approval process that launched the initiative.

Define Specific Next Steps

What are the first three concrete actions required with specific deliverables for the next 30/60/90 days? Who needs to be involved in execution, and what handoffs are required?

Questions to ask

What early indicators would signal we're off track and need to course-correct?

This builds early warning systems into the plan. If certain milestones slip, if key assumptions show signs of breaking, if resource constraints emerge - surface these triggers now so the owner knows when to escalate.

Set Realistic Deadlines

What are the deadlines for major milestones aligned with planning cycles? Which deadlines are immovable constraints versus aspirational targets?

Resource questions that matter

What resources freed from stopped initiatives enable us to meet these deadlines?

This connects your stopping decisions to execution capacity. If you're launching three new initiatives but haven't stopped anything, you're setting up resource conflicts that guarantee delays.

Identify Dependencies and Risks

What must happen before work can begin, including cross-functional and external dependencies? What critical dependencies could block or delay execution?

Plan for failure

What's our mitigation plan if critical dependencies fail to deliver? If the platform migration you depend on slips by two quarters, what's plan B? If the partner you're counting on backs out, what alternatives exist?

Building contingencies upfront is faster than scrambling when dependencies break.

Establish Accountability

How will you track progress between strategy reviews? Monthly updates? Quarterly deep dives?

Decisions for accessible and actionable documents

A clear record of what you decided, why, who owns it, and when it's due. The best organizations use simple formats: initiative name, owner, objective it supports, key milestones, kill criteria, next actions with deadlines.

How ITONICS enables decision-ready strategy reviews

ITONICS was built specifically for innovation and R&D strategy execution. The platform consolidates horizon scanning, technology monitoring, competitive intelligence, and portfolio data into a single workspace (Exhibit 4).

Exhibit 4: The ITONICS innovation methodology

Market trends, emerging technologies, and internal project performance become accessible without jumping between systems. This eliminates the pre-review scramble where teams waste days compiling data from disconnected sources.

The platform mirrors how innovation leaders actually think - providing structure where it helps and flexibility where innovation demands it. You spend less time wrangling data and more time debating what matters.

- Strategy reviews require discipline, not just tools. Technology enables sustainable practice but doesn't replace clear objectives, honest evaluation, or the courage to make hard choices. Position ITONICS as the enabler of discipline, not a substitute for it.

- The real problem is coordination, not capability. Teams know how to run good strategy reviews. They struggle with data consolidation, assumption tracking across time, and connecting strategic decisions to portfolio execution. ITONICS solves coordination problems that manual processes can't scale.

- Innovation strategy is fundamentally different from business planning. Traditional planning tools assume linear execution and stable assumptions. Innovation demands scenario planning, assumption testing, and portfolio balance between exploration and exploitation. ITONICS was purpose-built for this reality.

- Decision-forcing processes need decision-supporting infrastructure. The four-step checklist outlined in this article only works if teams can actually access the data to validate objectives, track assumption evidence, evaluate portfolio balance, and document decisions with accountability. ITONICS provides that infrastructure without requiring teams to build custom systems or maintain complex spreadsheets.

Ready to transform how your organization connects strategy to execution? Explore how ITONICS enables integrated strategic roadmapping, innovation management, and portfolio governance.

FAQs on running a strategy review

How is a strategy review different from a quarterly business review?

A strategy review questions whether the current strategy still makes sense.

A quarterly business review evaluates how well teams executed an existing plan.

Strategy reviews focus on strategic objectives, assumptions, and resource allocation decisions. Business reviews focus on performance metrics and variance to plan.

What decisions should a strategy review explicitly produce?

A strategy review must result in clear yes or no decisions. These include validating or revising strategic objectives, stopping initiatives that no longer fit, approving new initiatives with committed resources, and assigning ownership with deadlines.

If no decisions are made, the review failed regardless of discussion quality.

Who should participate in a strategy review to ensure real outcomes?

Only decision makers and critical advisors should attend.

-

Decision makers control resources and must be able to commit to change.

-

Advisors such as R&D leaders, finance, or market experts provide evidence and challenge assumptions.

-

Large groups dilute accountability and reduce decision quality.

How often should organizations run strategy reviews in innovation and R&D contexts?

Most innovation-driven organizations need a dual rhythm.

-

Run deep strategy reviews twice per year to reassess objectives and allocation.

-

Use lighter quarterly check-ins to monitor assumptions and emerging risks.

-

Trigger ad-hoc reviews when market, technology, or regulatory conditions materially change.