Pharma partner programs face a costly pattern-matching failure. You've signed strategic alliances with prestigious names. You launched innovation collaborations. You built extensive networks. Yet, 60% of pharma co-developments fail to deliver value.

The best way to prevent costly mistakes is not to collaborate when there is no benefit or better alternatives. Most large enterprises burn $50M+ annually on external developments that create overhead instead of outcomes.

Exhibit 1: The $50M partnership tax breakdown

Biogen's 2023 restructuring revealed $43M in partnership termination costs alone. When you factor in the pre-termination overhead, coordination costs, and opportunity costs of resources tied up in failing partnerships, the actual partnership tax likely exceeded $70M. For top-10 pharma companies, that number could scale to $400M-1B.

This article breaks down:

-

The three failure patterns draining resources (innovation by default, prestige over performance, portfolio chaos)

-

Three questions that prevent expensive mistakes before signing (build-vs-buy analysis, selection criteria, execution setup)

-

Four pre-meeting tests that expose problems early (one-sentence clarity, walk-away thresholds, internal resistance, portfolio capacity)

-

Real decision frameworks: when building internally beats external development, how to measure ROI before outcomes materialize, and why portfolio thinking prevents the $50M partnership tax

Where most pharma partnerships burn money

Partnerships fail in predictable patterns. Three patterns appear repeatedly across failed deals, wasted spend, and portfolios that look impressive but deliver nothing.

Identifying these predictable patterns early is crucial to preventing wasted spend and failed deals.

Innovation imperative: Partnering by default, not by need

Pharma operates under constant pressure to innovate. When internal pipelines thin, the reflexive response is: “We need more external input.” External innovation becomes the default answer before anyone asks whether it’s the right answer.

This is partnering by default, not by need. Nobody evaluates whether building the capability internally, such as investing in software development, would cost less, deliver faster, or create more competitive advantage.

The alliance happens because “we’ve always joined forces for this” or because it’s easier to get budget approval for external collaboration than internal headcount.

The result? Companies outsource for capabilities they should own.

They pay ongoing costs for critical competencies that competitors build once and leverage forever. Three years in, they realize they’ve spent more on agreement overhead than building in-house would have cost, and they still don’t own the capability.

Prestige trap: Strategic partnerships looking good to other stakeholders

Some partnerships exist to impress board members, investors, or the market. Collaborating with a prestigious name signals credibility. It makes the quarterly earnings call sound strategic. It reassures stakeholders that the company is "doing something" about innovation.

These team-ups optimize for optics, not outcomes. The co-developer contributes more brand than commercial value. Decisions take months because everything requires alignment. Resources get allocated to managing the relationship instead of advancing the science.

The tell: If your partnership generates more press releases than milestones, you're in the prestige trap. You've bought insurance against looking incompetent, not a third party who makes you more competent.

Portfolio problem: Managing vendors one-by-one instead of as a portfolio

Most pharma companies evaluate collaborations individually. Each deal gets its own business case, its own approval process, its own efficiency metrics. Nobody asks: “How does this fit with our other relationships? Are we over-committed? Do we have three start-up contractors doing overlapping work?”

The result is portfolio chaos. Business units optimize locally while the company bleeds globally. You discover you’re paying three different companies for similar capabilities. You have market engagements requiring 10 hours of coordination weekly, but only two people are managing them. You develop new startup relationships faster than you can absorb them. A major contributor to this chaos is the absence of a centralized system for managing partnerships, which leads to inefficiencies and redundancies.

Companies managing 15+ contractors successfully have one thing in common: they manage them as a portfolio. They have clear criteria. Full visibility. And, each buy decision ties to concrete strategic benefits.

The three questions that follow prevent all three patterns.

Three question framework for build-buy decisions

The difference between companies that waste millions and those that don’t comes down to three questions. Ask them before signing, and you’ll catch expensive mistakes. Skip them, and you’ll discover the problems after the costs are sunk.

Exhibit 2: Three question framework for partnering decisions

Each category eliminates a category of partnership waste. It's a filter. Together, they force clarity on what most companies decide through momentum and politics. This framework also ensures you evaluate the right solution for your organization’s needs, considering capabilities, integration, and long-term suitability.

Question 1: With whom should we partner, at all? This catches the build vs buy decision nobody makes. Most collaborations happen because “we need innovation fast” or “we lack this capability.” But faster than what? Compared to building it how?

Without answering whether internal development makes more business sense, you’re teaming up by assumption.

Question 2: Is this the right partner, for how long? This separates allies who create value from those who just reduce your risk. Some engagements exist so nobody gets blamed if things fail. Others exist because the vendor’s capabilities genuinely accelerate your goals.

The difference shows up in costs, speed, and whether you’re solving critical problems or just creating coordination overhead.

Question 3: Are we set up to deliver together, fast enough? This catches the collaboration failures before they happen. You need to develop clear performance metrics, defined decision rights, agreed tools, and routines.

They’re the difference between co-development programs that ship products or meeting notes.

Each question maps to a phase: deciding whether to collaborate, selecting the right vendor, and setting up for successful delivery. Miss anyone, and you’ve built the $50M partnership tax into your business operations.

The next three sections break down exactly how to answer each question.

Question 1: With whom should we collaborate - at all?

Most pharma companies skip this question entirely. They start with “which vendor should we choose?” before answering “should we outsource at all, or develop a custom solution in-house?” This costs millions in wasted resources and capabilities you pay for repeatedly instead of owning once.

Critical functionality view: Does this fill a strategic gap or create overlap?

Map your existing capabilities before evaluating any option. What critical functions do you already have in-house? What are you building internally? What have you joined forces for previously?

The dangerous pattern: co-developing for capabilities that overlap with internal development or existing solutions. You end up paying external costs while your internal teams build the same thing. Neither effort gets full resources. Both deliver late.

Ask: Does this alliance fill a gap we can't close internally, or does it duplicate work already happening?

If three business units are exploring similar start-ups for related technology, you're creating expensive redundancy.

The strategic gap test is simple. If losing this capability would stop you from competing in a critical market, and you can't build it in a reasonable timeframe, it's a gap worth filling externally. Everything else is a "nice to have" that probably belongs in your internal development pipeline.

Development approach: When building it internally is superior to strategic partnerships

Building internally costs more upfront but less over time.

Working with third parties costs less upfront but creates ongoing expenses: coordination overhead, license fees, dependency costs, integration complexity, and significant ongoing maintenance.

Ongoing maintenance includes updates, support, enhancements, and managing software end-of-life, all of which contribute to long-term costs. Make or buy is a business decision with clear antecedents.

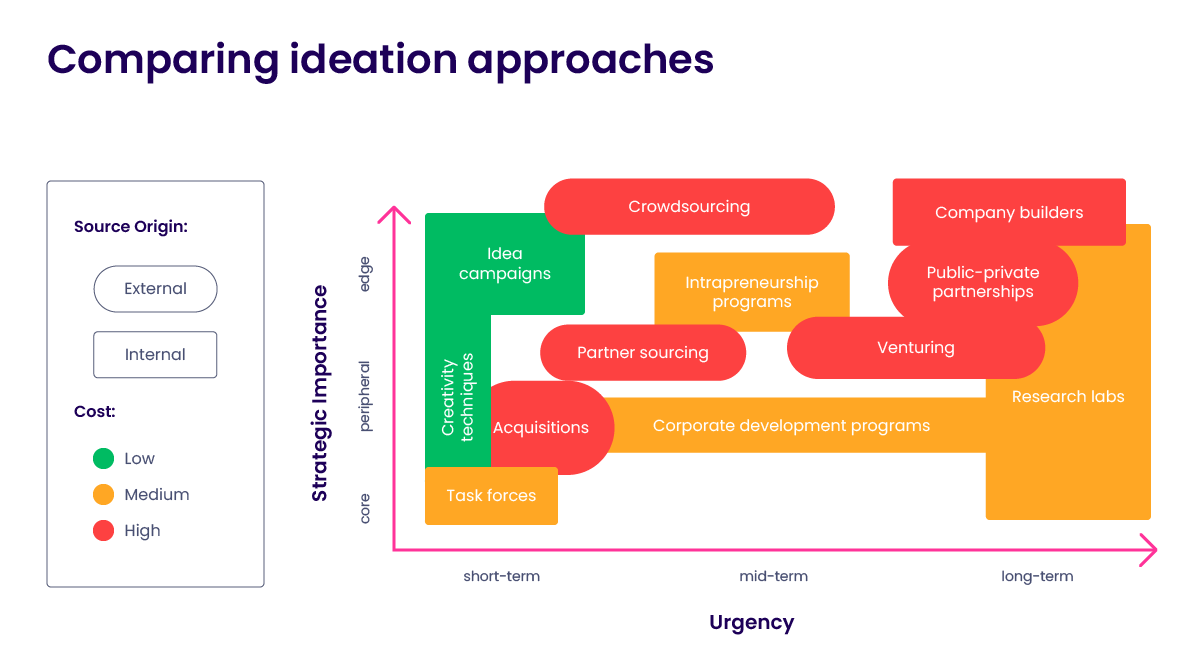

Exhibit 3: Comparing development approaches by importance and urgency

Run the math across five years, not one. A $2M internal build might beat a $500K annual collaboration that costs $3M over the same period and leaves you dependent on external technology you don’t control.

Building internally wins when:

-

The capability is central to your competitive advantage

-

You’ll use it repeatedly across multiple products or markets

-

The technology is stable enough that building once makes sense

-

Speed to market isn’t the primary constraint

Collaborations win when:

-

You need the capability once or infrequently

-

The technology changes faster than you can maintain internally

-

Time to market justifies the ongoing costs

-

The partner’s expertise would take you years to develop

The buy decision defaults to partnerships because budget approvals favor external spend over headcount. Fight this bias.

Calculate the total cost of ownership, not just Year 1 expenses.

Red flags in the discovery phase

Stop the partnership process immediately if:

-

Nobody can articulate what you'd lose by building internally. If the answer is "it would take longer" without defining how much longer or what that delay costs, you haven't done the analysis.

-

The business case compares costs to a theoretical internal build that nobody scoped. Vague estimates ("building this would cost $5M and take three years") aren't decision-grade data.

-

Three people in the room think you already have this capability or something close to it.

Question 2: Is this the right partner - for how long?

Choosing the wrong vendor costs more than choosing none. Companies waste years on external engagements that look impressive but deliver nothing.

The key differentiators between successful and failed collaborations show up in how you select partners, whether you’re honest about dependency, and whether the third party has well-developed tools or materials to support your goals.

Partner selection: The criteria to select the best allies with confidence

Start with business goals, not brand names. What specific outcome must this partnership achieve? Revenue generation? Time to market acceleration? Access to critical functionality you can't build? If you can't state the goal in one sentence, you're not ready to evaluate partners.

Evaluate candidates on three non-negotiable criteria:

Capability match. Can they actually deliver what you need? Don't accept case studies from other stakeholders or press releases about innovation. Demand real-world examples: Who have they done this for? What were the project timelines? What were the results?

Incentive alignment. Do they make more money when you succeed, or when the engagement drags on? Biopharma companies often co-innovate with tech companies whose revenue model rewards long-term consulting, not fast delivery.

Resource commitment. Will you get their best team or whoever is available? Document automation, building software, and custom solutions, these require dedicated resources. If the firm can't commit specific people with relevant expertise, you're buying a brand name that will deliver junior staff.

/Still%20images/Element%20Mockups%202025/ideation-collaborative-communities-2025.webp?width=2160&height=1350&name=ideation-collaborative-communities-2025.webp)

Exhibit 4: Evaluating partners on transparent criteria (see collaborative ratings in action →)

The convincing case for contracting includes their track record on core product development in your therapeutic area, their approach to reducing costs without sacrificing quality, and proof that they've helped similar companies achieve crucial decisions faster.

Dependency view: Strategic partnership or tactical collaboration?

Strategic partnerships create long-term dependency. You integrate their technology into your core product. You rely on them for maintenance burden management. They become embedded in your operations. This makes sense when the capability is non-core but critical, like specialized building in-house infrastructure you use continuously.

Tactical collaborations solve discrete problems. You need specific expertise once, then move on. No vendor lock-in, no ongoing overhead, minimal stakeholder buy-in required.

The mistake: treating tactical needs as strategic partnerships. You create document automation or build software dependencies for one-time projects. Three years later, you're paying annual fees and coordination costs for capabilities you barely use.

Ask: If this company disappeared tomorrow, would it stop our core operations or delay one project? That tells you if it's strategic or tactical.

Red flags in vendor selection

Walk away if the vendor can't demonstrate user satisfaction from comparable companies. Walk away if they promise cost efficiency improvements but can't show data. Walk away if achieving potential advantages requires you to change your entire tech stack to match theirs.

Walk away if every answer includes "generative AI" or buzzwords that don't map to your actual needs. Walk away if they need eight time zones of approvals for simple decisions.

And walk away if the partnership creates hidden costs through integration complexity, nobody scoped upfront. Increase productivity claims mean nothing without proof of new revenue potential or time to market improvements in contexts like yours.

Question 3: Are we set up to deliver together - fast enough and at scale?

Most partnerships fail in execution, not strategy. Companies choose the right capability and the right collaborator, then sabotage delivery with unclear accountability, mismatched systems, and success criteria nobody can measure.

Setting up properly before work begins determines whether you build solutions or accumulate costs. The benefit of clear execution is that it maximizes partnership outcomes, ensuring goals are met efficiently and effectively.

Planning accountability: Defining partnership roadmaps

Clear roadmaps prevent the meeting spiral. Define what gets delivered, when, and who owns each milestone. Vague commitments like "we'll collaborate on research and development" create confusion. Specific roadmaps state: "Phase 1 delivers prototype by Q2, Phase 2 completes market validation by Q4."

/Still%20images/External%20Webpage%20Mockups%202025/ideation-share-your-product-plans-2025.webp?width=2220&height=1410&name=ideation-share-your-product-plans-2025.webp)

Exhibit 5: Develop shared development roadmaps with ITONICS (see roadmap planning in action →)

Accountability requires names, not departments. "The innovation team will handle this" means nobody will. Identify who makes crucial decisions on each side. Who approves changes to the scope? Who controls the budget? Who resolves conflicts when priorities shift?

Build decision frameworks upfront. A map that requires joint approval versus independent action. Example: Technical architecture decisions might need mutual agreement, while tactical execution decisions don't. This prevents bottlenecks where simple choices take weeks because nobody knows who can decide.

Define how you'll evaluate progress. What data will you track? How often will you review it? What triggers course correction? Companies that succeed establish clear metrics (e.g., time to market improvements, cost reductions, customer adoption rates) and review them constantly, not quarterly.

Agreeing on collaboration tools, routines, and success criteria

Mismatched systems kill productivity. One side uses tool X, the other uses tool Y. One shares data through secure portals, the other emails spreadsheets. Integration complexity compounds until coordination costs more than the value created.

Agree on core tools before starting: communication platforms, project management systems, data sharing solutions, and document repositories. Don't let each team use their preferred tools. Or,do you like information silos and duplicated work?

Establish routines that scale. Weekly syncs work early but become unmanageable as teams grow. Define communication protocols: What needs real-time discussion? What can be asynchronous? When do you escalate issues?

Performance criteria must be observable and non-negotiable. "Improve efficiency" is meaningless. "Reduce development cycle time by 30%" or "Launch in three new markets within 18 months" gives you something to measure. Define what "good enough" looks like so you know when to stop iterating and start shipping.

/Still%20images/External%20Webpage%20Mockups%202025/ideation-collect-external-ideas-2025.webp?width=2220&height=1410&name=ideation-collect-external-ideas-2025.webp)

Exhibit 6: Create ITONICS webpages to collect partnership proposals (see venture clienting in action →)

Red flags in collaboration setup

Stop if the other side can't identify who on their team will actually do the work. "We'll assign resources as needed" means they're overcommitted and you'll get whoever is available, not who is qualified.

Stop if they want to "figure out tools and processes as we go." That's code for "we haven't done this before and hope it works out." Established collaborators have proven systems and can show you examples from similar engagements.

Stop if performance criteria discussions turn political. If they resist defining measurable outcomes, they're protecting themselves from accountability. Real research partnerships define clear insights to generate. Real development partnerships commit to specific delivery timelines.

Stop if their proposal requires you to adopt their entire technology stack or abandon existing solutions that work. Integration should be bidirectional, not a forced migration that increases your costs while locking you into their systems.

What to do before your next partnership meeting

Stop preparing slide decks. Start preparing questions. The companies that avoid expensive mistakes don't have better presentations, they have better decision-making process filters. Before you walk into the next meeting, run four tests that expose hidden costs and problems before they consume millions.

One-sentence test

If you can't explain what success looks like in one sentence, you're not ready to meet. Try it right now:

"This collaboration will deliver [specific outcome] by [specific date], which enables us to [specific business impact]."

Can't do it? That's your answer. Vague goals like "explore market opportunities" or "strengthen innovation" mean nobody knows what benefits they're actually buying. Real-world examples of successful strategic relationships always have simple success statements: "Launch in three European markets by Q4" or "Reduce long-term manufacturing costs 20% within 18 months."

The one-sentence test reveals whether this will lead to real outcomes or just activity that looks strategic. If the sentence requires three subclauses, the collaboration will require endless alignment meetings and produce nothing measurable. Effectiveness requires clarity. Press enter on partnerships that can't pass this test.

Walk away number test

Define your maximum investment before the meeting. What's the most you'll spend in costs, time, and resources before you stop? Write it down:

"If we spend more than $X or more than Y months without achieving [specific milestone], we terminate."

Most companies never set this threshold, so they keep funding failing partnerships because "we've already invested so much." The walk-away number prevents sunk cost thinking and protects you from hidden costs that emerge during execution.

Focus on total cost, not just contract value. A $500K partnership that requires $2M in internal resources to manage isn't delivering cost savings; it's creating efficiency drains. Example thresholds: "No more than $2M in Year 1 without completing Phase 1 trials" or "No more than 6 months without signed customer commitments."

Internal resistance test

Identify three stakeholders who will fight this partnership. Write down their objections. If you can't counter their concerns with data, your collaboration will die in internal politics, even if it's strategically sound.

Common resistance patterns:

- Operations teams worry about efficiency impacts and whether this will slow existing workflows.

- Finance questions long-term cost projections and whether claimed benefits are realistic.

- Business unit leaders fear losing control or resources.

- End users resist adopting new technology or processes that change how they work.

If you can't get internal buy-in before the external meeting, you're wasting everyone's time. The partnerships that succeed have resolved internal objections before signing external agreements. Strong strategic relationships require internal effectiveness first.

Portfolio health check

Before adding another engagement, audit what you already have. List every active collaboration. For each one, answer:

Can you identify the person accountable for developing and delivering results?

If it's "the team," nobody is accountable. That's a failing partnership consuming resources without producing outcomes.

Exhibit 7: Startup portfolio list in ITONICS (see in action →)

Has it hit a major milestone in the last 90 days? If not, it's stalled. Stalled partnerships rarely recover. They just generate overhead costs while everyone hopes they'll improve without anyone taking action.

Would you sign this deal again today, knowing what customers actually need and what the market demands? If no, that's data. Cut it and reallocate resources to collaborations that create content, solve real problems, and deliver measurable value.

Most companies discover they're managing too many partnerships badly instead of fewer partnerships well. The goal isn't maximizing the number of strategic ties, it's maximizing actual benefits from the right ones.

FAQs on pharma partnership programs

How do you measure collaboration ROI in pharma when outcomes take 5-10 years?

Don't wait for revenue. Track leading indicators quarterly: Are milestones hitting on time? Are decisions taking weeks or months? Is the third party contributing resources or just attending meetings?

The best early signal is decision velocity. Healthy partnerships make faster decisions than you would alone.

Set 12-month checkpoints with binary outcomes: "Did we advance the asset to the next stage?" If you can't point to tangible progress annually, the financial ROI won't matter.

When should you terminate a co-development instead of trying to fix it?

Terminate when the cost of staying exceeds the cost of leaving. Three signals make this clear:

Misaligned incentives that can't be fixed. If your ally profits from delays while you need speed, no meetings will resolve this.

Sunk costs exceed realistic future value. If you've spent $8M and the joint venture might generate $5M, you're chasing losses.

Partner capability has degraded. Key people left, priorities shifted. The other party you signed with no longer exists.

How many pharma partnerships can a company effectively manage at once?

Count partnerships requiring weekly coordination. If that number exceeds your available partnership managers by 3:1, you're stretched too thin.

The warning sign? When your team says "we need another partnership" but can't name which existing one they'd cut to make room.

Companies managing 15+ partnerships well have centralized functions and quarterly portfolio reviews. Everyone else should probably cut half and double down on what's working.

Should pharma companies have a centralized partnership function or let business units manage their own?

Distributed management feels faster but creates blind spots. You end up with overlapping capabilities, and nobody sees the full picture.

The hybrid model works best: Centralize strategy and portfolio oversight, distribute execution. A central team sets criteria and has veto power on overlapping deals. Business units own delivery.

This requires executive sponsorship with teeth. If business units can bypass the partnership office, you're back to chaos with extra overhead.