Seventy percent of technology initiatives fail not from technical flaws but from lack of internal buy-in. Project Management Institute research confirms the pattern: superior technical solutions lose to inferior alternatives that navigate organizational dynamics better. The gap between merit and adoption drives massive waste in corporate technology spending.

Yet technology managers face a mismatch between training and reality. Their education emphasizes system architecture and flawless execution; their success depends on stakeholder management and influence across functions they don't control. Effective leaders must fully understand both technical and organizational management systems to advance their initiatives and careers.

One chief technology officer at a leading pharma organization summarized it: "I can architect a system in three weeks. Getting twelve executives to agree it's worth funding takes six months." Technology leaders responsible for emerging technology development face this challenge daily.

Buy-in is a structured process with identifiable stages and repeatable tactics. It requires leadership skills and effective communication that extend beyond technical expertise.

This blog presents a four-phase framework for securing support before committing resources:

-

-

Map Your Territory by identifying decision makers, gatekeepers, and amplifiers,

-

Build Incremental Commitment through staged artifacts and social proof,

-

Orchestrate the Decision Point via strategic pre-conversations, and

-

Sustain and Scale Adoption through leading indicators and champion networks.

-

Beyond these core phases, we also cover advanced tactics, including the technology translation layer for adapting messages to different stakeholders and recovery strategies for when initiatives hit unexpected resistance. Leaders who apply this systematic approach compress decision cycles, reduce rework, and deliver solutions that organizations actually implement.

Why technical excellence isn't enough

Technical merit predicts less than 30 percent of project approval outcomes in enterprise organizations. Harvard Business Review research on IT project success confirms this gap. The remaining 70 percent reflects organizational dynamics: perceived risk, implementation friction, and stakeholder alignment.

Success requires knowledge of both technical and organizational systems, with data to support decision-making.

A solution that reduces processing time by 40 percent can lose to one that threatens fewer workflows, even when the faster option demonstrates superior ROI. Disruption concerns often outweigh efficiency gains in organizational decision-making.

Effective technology managers recognize that decisions reflect how organizations weigh change against gains when multiple stakeholders hold veto power. Communication skills matter as much as technical capability.

The pattern: Superior solutions that never ship

Gartner tracked enterprise technology projects and found that 55 percent with strong technical validation failed to launch due to organizational resistance. This pattern repeats across industries, company sizes, and business contexts. Teams in enterprises and small businesses face similar challenges despite different scales.

The progression is familiar: technology managers build proof of concepts that exceed requirements, pilots demonstrate measurable improvements, and proposals enter approval with sponsor support. Then the momentum shifts. Questions multiply, integration complexity surfaces, resource allocation debates begin, and competing priorities emerge. Decisions defer to next quarter, then next year.

Projects die from inertia rather than explicit rejection. Organizations rarely say no to superior solutions outright; instead, they delay them into irrelevance while politically simpler alternatives advance. This happens because internal processes favor familiar approaches over innovative ones. Three specific failure modes explain why even well-validated proposals stall.

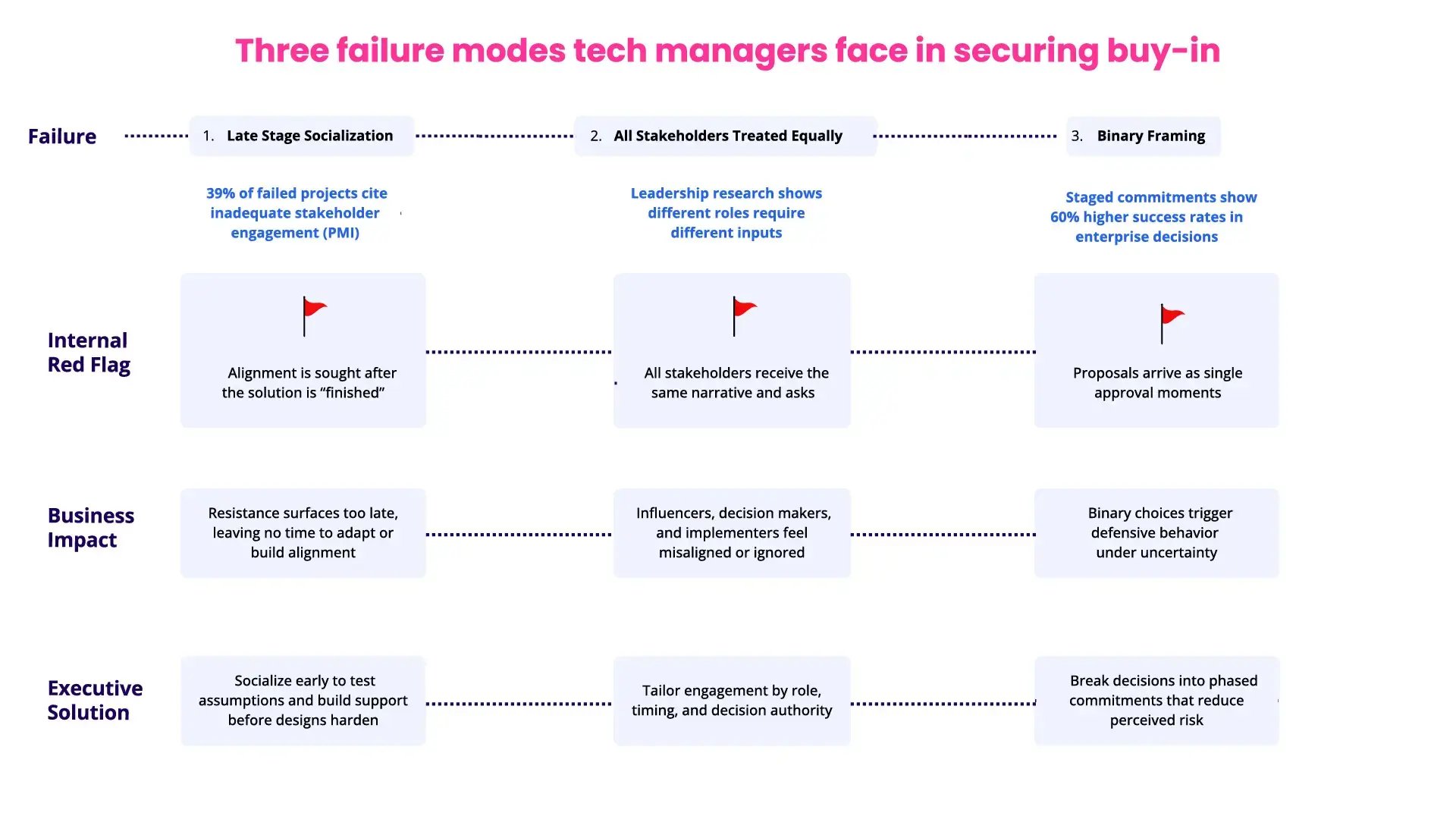

Three failure modes tech managers face in securing buy-in

The first failure mode is late-stage socialization.

PMI research found 39 percent of failed projects cite inadequate stakeholder engagement as the primary cause. Technology managers and project managers alike perfect solutions before building support. By the time they socialize proposals, insufficient runway remains to address resistance.

The second mode treats all stakeholders equally.

Influencers, decision makers, and implementers need different engagement at different moments. Uniform communication satisfies no one. Leaders who manage these relationships with precision, using problem-solving skills and the right tools for each stakeholder type, strengthen their organization's decision-making capacity.

The third is binary framing.

A study of 500+ enterprise technology decisions found that proposals framed as single approval points had 60 percent lower success rates than those with staged commitments. When proposals arrive as yes-or-no choices, they trigger defensive responses. Executives facing uncertainty default to no.

Avoiding these failures starts with understanding the terrain before building the solution.

Exhibit 1: Three failure modes in securing buy-in, linking internal red flags to business impact, and corrective leadership actions.

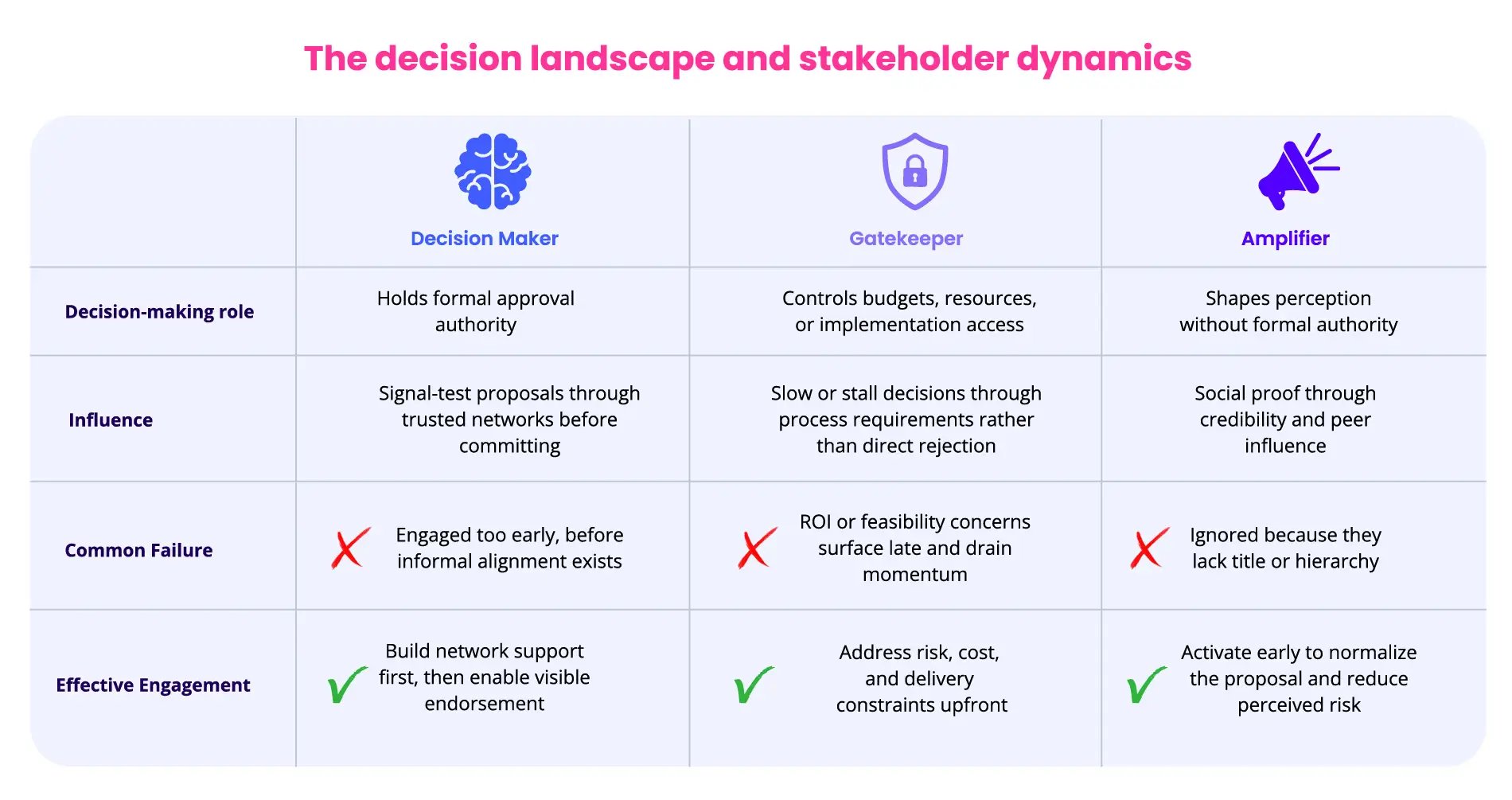

Understanding the decision landscape

Enterprise technology decisions involve 6.8 stakeholders on average, according to Gartner research. Each applies different criteria at different stages. Most technology managers map organizational charts instead of influence networks.

This explains why technically sound proposals fail despite C-suite sponsorship. Real decisions happen through informal coalitions, perceived risk, and concerns about implementation difficulty. Success requires distinguishing between three stakeholder types that wield influence differently.

Stakeholder management: Decision makers vs. gatekeepers vs. amplifiers

Three stakeholder types determine outcomes. Each requires distinct engagement.

Decision makers

Decision makers hold formal approval authority but rarely act without consensus signals from their networks. A CIO or VP of R&D needs air cover before endorsing a proposal publicly. They test reactions in smaller settings first.

Technology managers who treat decision makers as the first point of contact miss the foundation-building phase that matters most. Success depends on the ability to create and maintain relationships with the broader network first.

Gatekeepers

Gatekeepers control access to resources, budgets, or implementation capacity. A finance director questioning ROI assumptions can freeze a project indefinitely. These stakeholders exercise veto power through process rather than position.

Rather than rejecting proposals outright, they introduce requirements that delay decisions until momentum dies. In services organizations, gatekeepers may control access to customers and client relationships, amplifying their potential impact on project outcomes.

Amplifiers

Amplifiers lack formal authority but shape perception across the organization. A respected engineering lead or product manager carries outsized influence through credibility and network reach. MIT research found that amplifiers affect 40 percent more stakeholders than their formal position suggests.

When amplifiers endorse a solution, they create social proof that reduces perceived risk for others considering the initiative.

Technology managers who engage all three types systematically compress approval cycles by 35 percent compared to those who focus only on decision makers. But identifying stakeholder types is only half the picture; you need to understand when each exercises influence.

Exhibit 2: The decision landscape, contrasting how decision makers, gatekeepers, and amplifiers shape buy-in and outcomes.

Decision journey archaeology: How tech choices actually get made

Technology decisions follow predictable patterns invisible in project plans. Stanford research tracking 200 enterprise software purchases found the real decision process started 4.7 months before the formal RFP. This early phase is when amplifiers set the tone and gatekeepers establish boundaries.

Early conversations set evaluation criteria and narrow consideration before procurement gets involved. Budget holders make provisional commitments in hallway discussions. Technical teams form preferences during pilots.

Each interaction represents a stakeholder exercising their specific type of influence at the moment it matters most. These informal processes determine outcomes more than formal approval workflows.

By the time proposals reach approval meetings, 70 percent of the outcome is already determined. The formal decision point ratifies consensus built incrementally through dozens of micro-commitments. Decision makers sign off on what amplifiers have validated and gatekeepers have cleared.

Understanding this invisible architecture is essential before entering the framework's first phase.

The four-phase framework for buy-in

The framework operates on a principle: commitment compounds through staged wins rather than single approval moments. Each phase reduces uncertainty for the next and aligns technology decisions with business goals.

Technology managers who execute all four phases reduce project approval time by 40 percent compared to those who jump directly to executive presentations, according to McKinsey research on enterprise decision-making.

Phase 1: Map your territory

Most technology managers start building before mapping influence. This creates blind spots that surface as objections during approval cycles.

Phase 1 inverts this sequence through a strategic approach: identify who holds formal authority, who controls resources, and who shapes perception before defining technical requirements. This requires analytical skills and discipline that traditional project management methodologies often overlook. Information technology leaders and their counterparts must understand business needs through data-driven analysis.

Two diagnostic tools make this systematic: the 3-5-20 prioritization matrix for stakeholder segmentation and pre-mortem analysis for surfacing resistance before it calcifies into opposition.

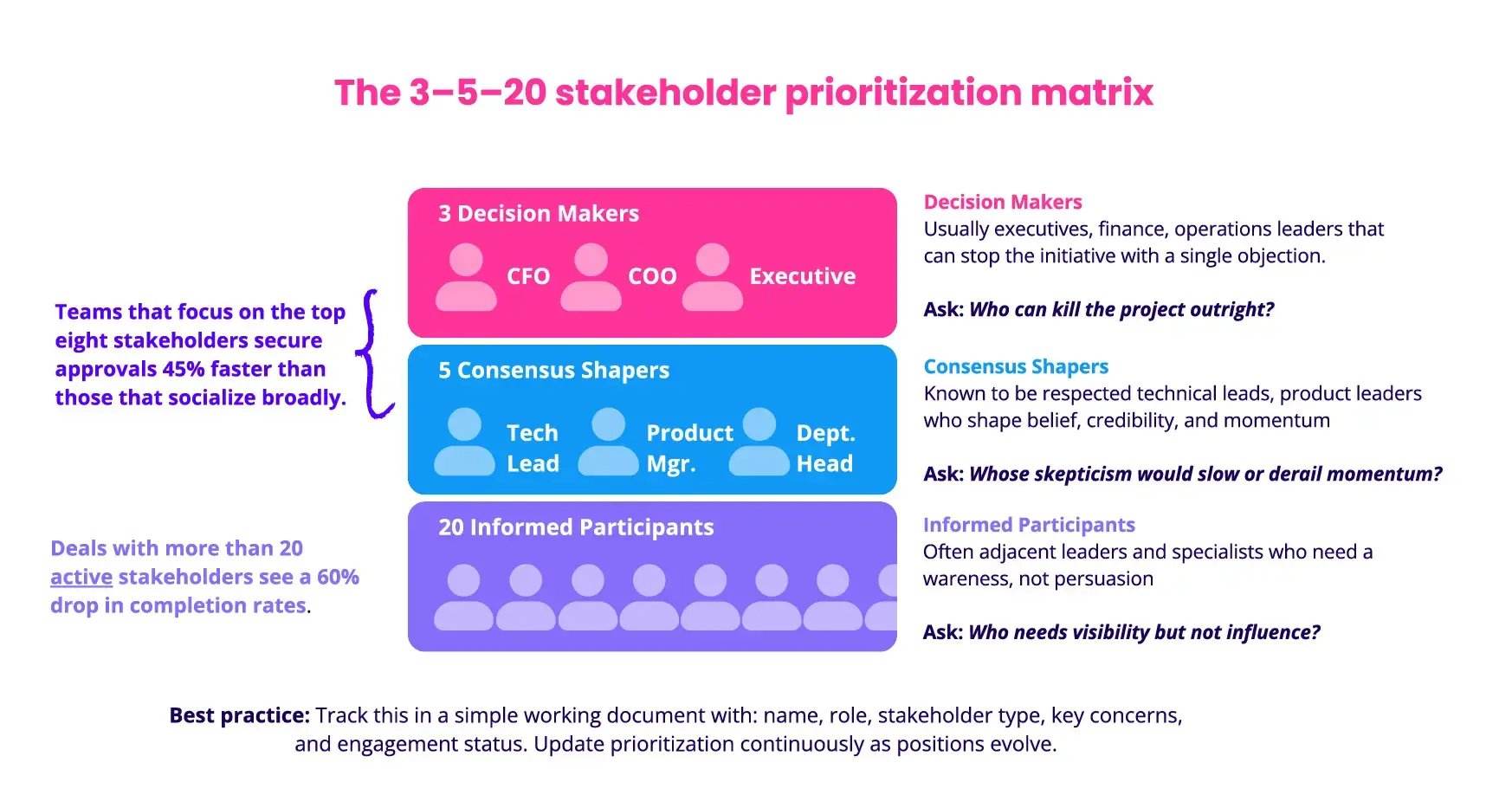

Identifying your 3-5-20: The stakeholder prioritization matrix

The 3-5-20 matrix segments stakeholders by influence tier. Three stakeholders have veto power over the decision. Five stakeholders shape consensus through credibility and network reach. Twenty stakeholders need awareness but lack decisive influence.

Bain research on enterprise buying found that organizations with more than 20 active stakeholders reduce purchase completion rates by 60 percent. Technology managers who concentrate effort on the top eight stakeholders (your three decision makers plus your five amplifiers) secure approvals 45 percent faster than those who socialize broadly.

Identify your three by asking: who can kill this project with a single objection? Finance directors controlling budgets qualify. Operations leads responsible for implementation qualify. The executive sponsor who must defend the allocation in leadership meetings qualifies.

Identify your five by asking: whose public skepticism would create organizational resistance? Respected technical leads and influential product managers qualify. The department head whose team will handle the heaviest implementation burden qualifies.

Identify your 20 remaining participants by asking: who needs to be informed but won't shape the decision? Department heads affected by implementation, adjacent team leads, and functional specialists fall into this tier.

Best practice is to document this matrix in a simple spreadsheet with columns for name, role, stakeholder type, key concerns, and engagement status. Update it throughout the initiative as you learn more about each person's position and priorities.

Exhibit 3: The 3–5–20 stakeholder prioritization matrix, showing how focus on key influencers accelerates approval and reduces decision drag.

Pre-mortem: Anticipating objections before they surface

Pre-mortem analysis surfaces objections when they cost nothing to address. Instead of asking what could go wrong, assume the project failed and work backwards to identify causes.

Run the session with two internal stakeholders who understand organizational dynamics. Ask: "It's twelve months from now, and this project never launched. What killed it?" Responses reveal political landmines, resource conflicts, and integration concerns that formal planning misses.

Conduct this session at least three months before formal proposal submission. This timeline provides sufficient runway to address identified concerns through solution adjustments or stakeholder pre-engagement. Best practice is to document findings in three categories: technical risks (addressable through design), resource risks (addressable through planning), and political risks (addressable through stakeholder engagement).

Phase 2: Build incremental commitment

Binary approval requests trigger defensive responses. Executives asked to commit funding without prior exposure default to caution.

Phase 2 replaces single approval moments with staged engagement that builds familiarity and reduces perceived risk through a progression of touchpoints.

The artifact ladder: Documents → demos → workshops

The artifact ladder sequences stakeholder engagement from passive to active participation. Each rung increases buy-in while revealing concerns early enough to address.

Start with brief documents that outline the problem and proposed approach. A two-page summary sent to your 3-5-20 stakeholders creates initial awareness without demanding meetings. Include relevant data that supports your case and demonstrates how the solution serves the organization. Best practice is to focus these documents on business outcomes rather than technical features. Translate system capabilities into workflow improvements or cost reductions.

Progress to demos once key stakeholders understand the context. A 20-minute working prototype demonstrates feasibility better than slide decks. For software development projects, show working code. For computer systems implementations, demonstrate integration points and security measures.

Invite your five amplifiers first. Their endorsement creates social proof and strengthens stakeholder management efforts. Technical skills matter, but relationship management skills determine adoption success. Best practice is to schedule demos as informal sessions rather than formal presentations. This encourages questions and reduces pressure on both sides.

Escalate to workshops for final refinement. A two-hour co-creation session with decision makers and gatekeepers converts them from evaluators to contributors. They identify integration requirements, suggest modifications, and build ownership through participation.

Cross-functional teams working together create stronger support than sequential review processes. Harvard research on organizational change found that stakeholders who participate in solution design are 70 percent more likely to support implementation.

With this foundation of incremental commitment established, the focus shifts to making adoption visible across the organization.

Exhibit 4: The artifact ladder, showing how documents, demos, and workshops build commitment and reduce perceived risk.

Social proof engineering: Making adoption visible across other teams

Stakeholders assess risk partly through peer behavior. When other teams adopt a solution without visible problems, perceived risk drops. This pattern holds across various industries from manufacturing to R&D.

Identify a low-risk team for initial deployment. Success here creates a reference case for broader adoption. Document specific outcomes with concrete metrics, not just "improved efficiency" but "reduced processing time from 45 minutes to 18 minutes per transaction."

Make the adoption visible through internal channels. Best practice is to work with pilot teams to create brief success stories for company newsletters, mention wins in leadership updates, and invite pilot participants to demo sessions with other stakeholders. Technology managers who engineer three visible reference cases before seeking enterprise approval face 50 percent fewer objections than those who propose organization-wide deployment immediately.

Phase 3: Orchestrate the decision point

The formal approval meeting may seem like the moment of truth, but in reality, it should ratify decisions made elsewhere. Phase 3 focuses on the real work: strategic pre-conversations in the 72 hours before the meeting.

McKinsey's analysis of enterprise buying decisions found that 80 percent of final outcomes were determined before participants entered the room. Organizations with strong data collection practices and effective project management identify this pattern early and plan accordingly.

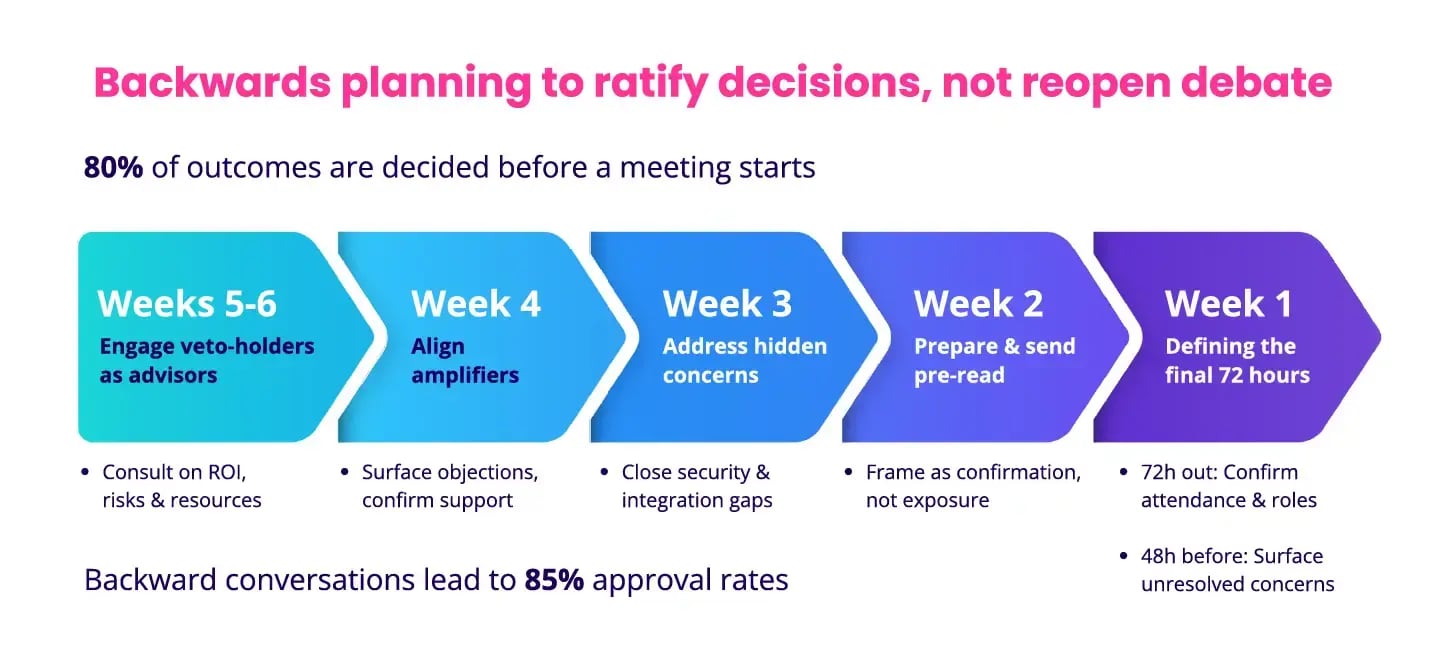

Backward planning from the decision meeting

Coordinating approval requires reverse chronology. Start with the approval date and work backwards to map required stakeholder conversations.

Backward planning starts six weeks before the target approval date:

Weeks 5-6: Focus on your three veto-holders through individual meetings. Engage them on resource management and implementation planning. Best practice is to frame these as consultation sessions where you're seeking their expertise on specific aspects, budget modeling with finance, rollout sequencing with operations, risk assessment with security. This positions them as advisors rather than gatekeepers.

Week 4: Engage your five amplifiers to ensure credible support. Leadership alignment happens at this stage. Best practice is to ask amplifiers what concerns they're hearing from their networks and what would make them comfortable publicly endorsing the initiative. This surfaces hidden objections while building their stake in the outcome.

Week 3: Handle remaining concerns from prior conversations. For IT infrastructure projects, address security measures and integration questions. Best practice is to document how you've incorporated feedback from weeks 4-6, showing stakeholders their input shaped the final proposal.

Weeks 1-2: Prepare decision makers with individual briefings and send a brief pre-read framing the decision as confirmation rather than first exposure.

This approach identifies misaligned requirements early. CFOs may need different ROI framing than COOs. Effective resource management and stakeholder coordination separate successful leaders from those who struggle.

Exhibit 5: Backward planning for approvals, showing how pre-meeting alignment drives faster, higher-confidence decisions.

The 72-hour rule: Meeting anatomy and strategic sequencing

The final 72 hours determine whether your approval meeting confirms consensus or devolves into debate. Best practice follows this sequence:

72 hours out: Confirm attendance and roles. If a key gatekeeper can't attend, reschedule rather than proceeding without their buy-in. A decision made without critical stakeholders present creates grounds for reopening discussions later.

48 hours before: Conduct brief pre-calls with decision makers to surface remaining concerns. Best practice is to ask directly: "What would prevent you from supporting this on Thursday?" Address any hesitations immediately rather than hoping they won't surface in the meeting.

24 hours prior: Send a one-page decision brief framing the meeting as confirmation of a direction that's been extensively vetted. Best practice is to structure this brief with three sections: decision required, recommendation with rationale, and key stakeholder endorsements.

Research from Bain found that meetings framed as confirmations had 85 percent approval rates versus 40 percent for meetings framed as first-exposure decisions. The orchestration work in these 72 hours makes this reframing credible rather than manipulative.

Phase 4: Sustain and scale adoption

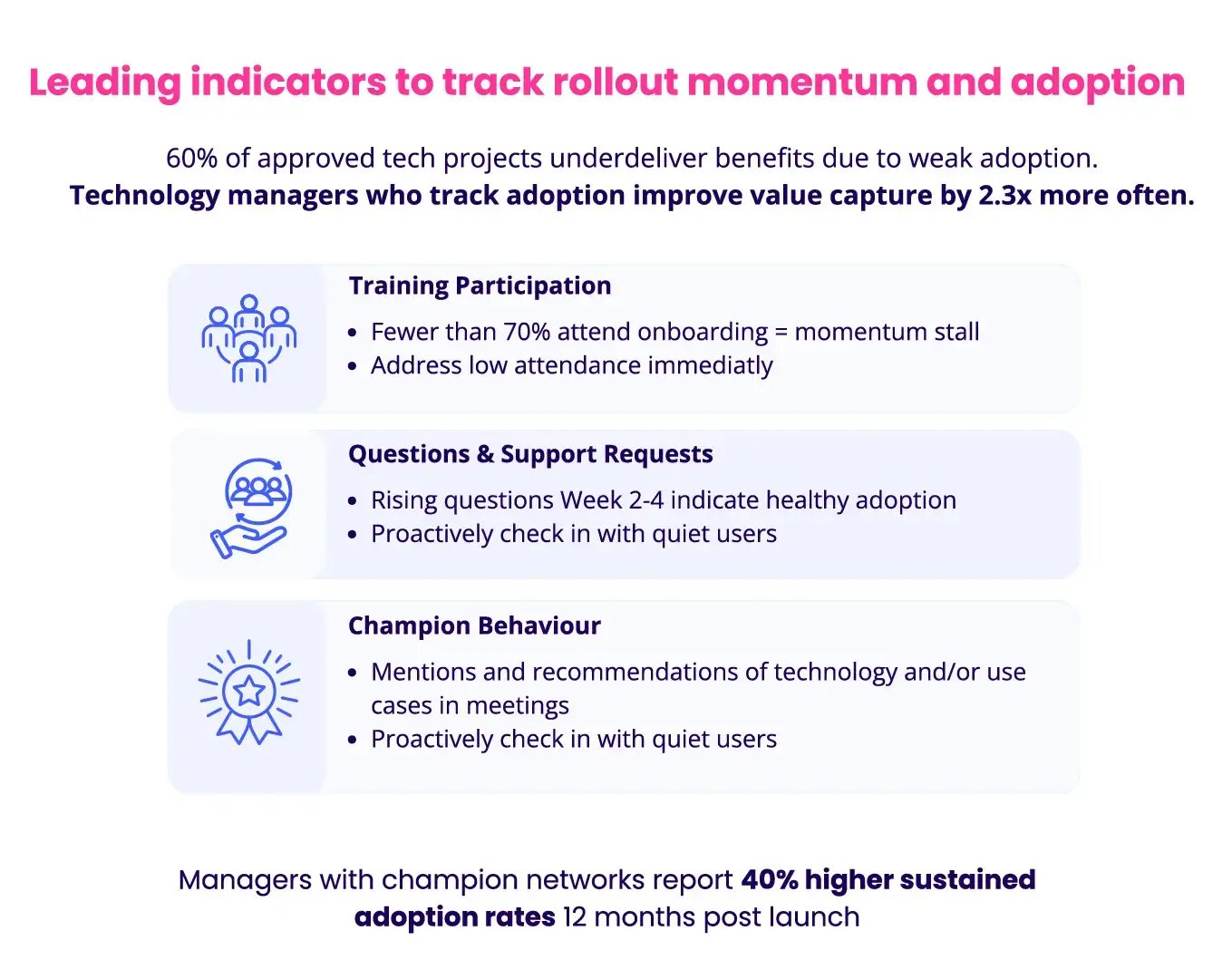

While the first three phases focus on securing approval, Phase 4 addresses an equally critical challenge: ensuring approved projects actually deliver value. Approval doesn't guarantee implementation. Success depends on the ability to sustain momentum through systematic tracking and support.

Gartner research found that 60 percent of approved enterprise technology projects underdeliver on promised benefits due to weak adoption. Technology managers who actively manage post-launch momentum capture projected value 2.3 times more often than those who assume approval ensures success. This requires knowledge of adoption patterns and intervention strategies.

Leading indicators of real adoption

Lagging indicators like utilization rates appear too late to correct course. Leading indicators predict adoption failure weeks before it becomes visible in metrics. Focus on collecting data across three signals:

Active participation in training and onboarding. If fewer than 70 percent of target users attend initial sessions, adoption will stall. Low attendance signals a lack of management emphasis or competing priorities. Address this immediately through leadership communication, reinforcing the initiative's importance.

Questions and support requests. Healthy adoption generates increasing questions in weeks two through four as users move from basic to advanced features. A drop in questions doesn't indicate mastery; it indicates users have given up or found workarounds. Best practice is to proactively check in with quiet users rather than assuming silence means satisfaction.

Champion behavior among early adopters. Champions spontaneously mention the tool in meetings, recommend it to peers, and identify new use cases. Best practice is to track this through brief monthly check-ins with your pilot teams, asking what they've heard from colleagues and where they've recommended the solution.

Track these three indicators weekly for eight weeks post-launch. When champion activity declines or support requests drop unexpectedly, immediate intervention through showcase sessions or leadership reinforcement prevents broader rollout failure.

Exhibit 6: Leading indicators that predict adoption success, showing how early signals help sustain rollout momentum and value capture.

Best practices for cultivating champions

Champions multiply your influence by advocating without your direct involvement. Effective stakeholder management creates a competitive advantage by accelerating adoption cycles. Developing champion networks is considered best practice across the industry. Three approaches separate effective champion cultivation from passive hope:

Identify champions early through pilot participation. The users who engage most actively during pilots, ask sophisticated questions, and suggest improvements are your natural champions. Best practice is to formalize this relationship through regular engagement structures like monthly councils, where champions share adoption strategies and surface implementation challenges. This creates a feedback loop that improves the solution while deepening champion investment.

Equip champions with assets that make advocacy easy. Create one-pagers explaining benefits, demo videos they can share, and talking points for common objections. Best practice is to develop these materials with champions rather than for them. They know which objections they're hearing and what formats their colleagues prefer. This co-creation ensures the assets actually get used.

Create visible recognition that reinforces champion identity. Mention champions in leadership updates and invite them to present at broader forums. This recognition supports their career advancement while reinforcing your initiative. Best practice is to position champions as innovation leaders rather than just users of your tool. Frame their involvement as evidence of forward thinking and organizational contribution.

Technology managers who implement all three practices report 40 percent higher sustained adoption rates twelve months post-launch compared to those who rely on organic advocacy. The four-phase framework handles most technology initiatives. Some contexts, however, require additional approaches.

Advanced tactics for maximizing buy-in

Enterprise-scale projects demand translation between technical and business languages. Projects that hit unexpected resistance need recovery strategies that salvage momentum without restarting from scratch.

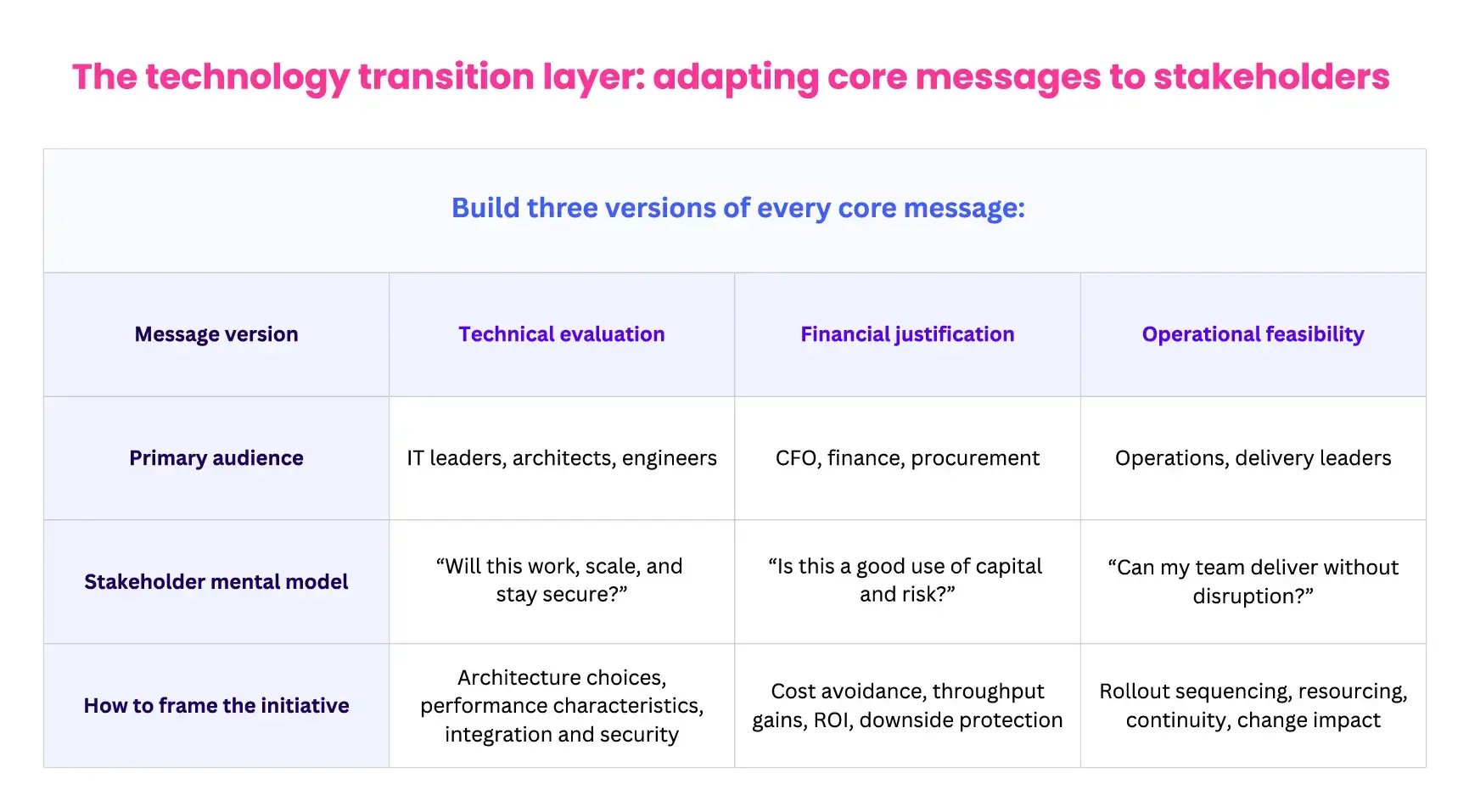

The technology translation layer

Technical accuracy doesn't guarantee stakeholder comprehension. Organizations increasingly rely on technology leaders who can bridge technical and business contexts. A chief information officer understands technical concepts differently from a CFO evaluating capital allocation. A VP of Operations assesses workflow disruption through a different lens entirely. Developing a deeper understanding of each stakeholder's decision criteria is essential.

The translation layer adapts core messages to stakeholder mental models without diluting technical substance:

For finance stakeholders: Frame proposals in capital efficiency, operational leverage, and risk-adjusted returns. Best practice is to translate technical improvements into financial metrics. Don't say "reduces latency by 200ms," say "enables processing 40 percent more transactions per hour without additional infrastructure costs."

For operations stakeholders: Emphasize process stability, implementation sequencing, and resource continuity. Best practice is to address their core concern directly: "How will this affect my team's ability to deliver during rollout?" Provide specific transition plans that minimize disruption.

For executive stakeholders: Focus on strategic positioning, competitive dynamics, and organizational capability. Best practice is to connect the initiative to board-level objectives. If the company is pursuing digital transformation, position your proposal as enabling that strategy rather than as a standalone IT project.

MIT research on cross-functional communication found that proposals adapted to stakeholder decision frameworks secured approval 50 percent faster than technically accurate but audience-agnostic presentations.

Build three versions of every core message: one for technical evaluation, one for financial justification, and one for operational feasibility. Technology managers fluent in programming languages and system architecture must develop equal fluency in business language to excel at stakeholder management. Deploy each version to the appropriate audience at the appropriate moment.

Exhibit 7: The technology translation layer, showing how core messages are adapted for technical, financial, and operational stakeholders.

Failure modes and recovery strategies

Even well-executed frameworks encounter unexpected resistance. Three failure modes appear most frequently, each requiring specific recovery approaches.

Emergent stakeholder opposition. A previously neutral gatekeeper suddenly raises objections late in the approval process. Best practice is to schedule a direct conversation within 48 hours. Delays allow concerns to spread and harden. Ask what changed and what information would address their hesitation. Often, the objection masks a deeper concern about resource allocation or implementation risk. Address the underlying issue rather than the surface objection.

Sponsor departure. Your executive champion leaves the organization or shifts roles. Best practice is to identify the natural successor within the sponsor's network before the departure becomes common knowledge. Brief them on progress to date and secure their conditional support before resuming stakeholder engagement. Frame this as continuity rather than starting over. The work done under the previous sponsor remains valid.

Pilot failure. Early adoption doesn't demonstrate expected value. Best practice is to run a structured post-mortem with pilot participants to identify root causes. Was it technical issues, inadequate training, poor change management, or misaligned expectations? Adjust the approach based on findings and communicate changes transparently to your stakeholder network. Credibility survives failure better than it survives cover-ups. Frame the pilot as successful learning rather than failed execution.

These tactics address specific challenges. The real test comes in consistent application across multiple initiatives.

From playbook to practice

Frameworks remain theoretical until applied systematically. The four-phase approach converts organizational influence from intuition into process.

Technology managers who execute this playbook build capabilities that compound across future initiatives. Each successful approval creates goodwill that makes subsequent projects easier. Each cultivated champion becomes a reusable asset. Each mapped stakeholder network provides a foundation for the next proposal.

The long game: Why this approach compounds velocity

Buy-in capabilities compound over time in ways technical skills don't. McKinsey research on organizational change found that technology leaders with three or more successful implementations secure approval 60 percent faster than those attempting their first major initiative. The difference isn't technical competence; it's accumulated social capital from taking time to build relationships and maintain good relationships across the organization.

The framework accelerates this compound effect by making relationship-building systematic. Following these approaches creates lasting advantages:

Your 3-5-20 stakeholder map becomes a living document updated across initiatives. The finance director, who was a gatekeeper on your infrastructure project, becomes an ally on your analytics initiative because you addressed their concerns thoroughly the first time. Best practice is to maintain stakeholder notes across projects, tracking preferences, communication styles, and previous objections to inform future engagement.

Your champion network grows with each successful deployment. Champions from one initiative become credible references for the next. Best practice is to stay connected with champions after project completion. They're valuable sources of organizational intelligence and potential advocates for future proposals.

Your pre-mortem insights reveal organizational patterns that inform future approaches. After three or four initiatives, you'll recognize which objections reflect legitimate concerns versus reflexive resistance, which stakeholders need early engagement versus late confirmation, and which organizational antibodies activate predictably. Best practice is to document these patterns and share them with other technology leaders, building organizational capability beyond your individual initiatives.

Technology managers who view internal buy-in as a long-term capability investment rather than a per-project task build influence that outlasts any single technology decision. This sustained influence separates those who advance to senior leadership from those who remain excellent executors of approved projects. Strategic relationship management distinguishes transformational leaders from operational managers.

Exhibit 8: ITONICS in-action, showing how systematic stakeholder interaction creates compounding buy-in and organizational memory.

Adapting the framework to your organization

No framework transfers perfectly across organizational contexts. Company culture, decision velocity, and stakeholder norms vary significantly between pharmaceutical R&D organizations, manufacturing technology teams, and software product groups. The framework scales from enterprise companies to small businesses, though resource constraints require different execution approaches.

Adapt the framework to your reality. If your organization moves faster than the six-week timeline suggests, compress the sequence while maintaining staged stakeholder engagement. The principle matters more than the specific duration. If formal approval meetings happen quarterly rather than on-demand, adjust the 72-hour rule to align with your actual decision cadence while preserving the concept of strategic pre-conversations.

The framework's value lies in its underlying logic:

-

Map influence before building solutions

-

Build commitment incrementally rather than requesting binary approvals

-

Coordinate decisions through preparation rather than persuasion

-

Sustain adoption through active momentum management

Best practice is to start with the full framework and track what works and what generates friction. Adjust based on evidence rather than assumptions. After three to four cycles, you'll develop a company-specific variant that maintains core principles while fitting your actual operating environment. Organizations that adapt thoughtfully see better outcomes than those applying generic templates. Successful portfolio management and resource management depend on this customization informed by your organization's unique dynamics.

FAQs about securing internal buy-in for enterprise technology initiatives

Why do technically strong technology initiatives fail to get approved?

Most technology initiatives fail because decisions are shaped by organizational risk, not technical merit. Approval outcomes reflect how leaders perceive disruption, ownership, and downstream accountability across functions they do not control.

Executives rarely reject proposals on substance alone. Instead, they delay decisions when alignment is incomplete or when uncertainty feels asymmetric across stakeholders.

High-performing technology leaders recognize that approval is not a presentation event but a multi-month alignment process. They invest early in shaping criteria, surfacing concerns, and building confidence before formal decisions occur.

Organizations that treat buy-in as a leadership discipline, rather than a communication task, reduce wasted effort and accelerate capital deployment. The difference is not persuasion skill. It is systematic preparation across the decision landscape.

How should executives think about stakeholder management in technology decisions?

Stakeholder management is not about consensus building or broad communication. It is about understanding who holds veto power, who shapes perception, and who quietly influences outcomes long before approvals are formalized.

Senior leaders often underestimate informal influence networks. Decisions emerge through pre-meetings, peer validation, and risk signaling rather than hierarchical authority alone.

Effective executives segment stakeholders by role and timing, not seniority. They engage gatekeepers on feasibility, amplifiers on credibility, and decision makers on strategic coherence.

This precision reduces friction and shortens decision cycles. Organizations that manage stakeholder influence deliberately avoid late-stage surprises and prevent technically sound initiatives from stalling due to unresolved concerns.

What is incremental commitment, and why does it outperform binary approvals?

Incremental commitment replaces single yes-or-no decisions with a sequence of smaller, lower-risk engagements. Each step builds familiarity, surfaces objections early, and reduces perceived downside.

Binary approvals force executives to absorb uncertainty all at once. Faced with incomplete confidence, most leaders default to caution rather than conviction.

Staged commitment distributes risk across time and stakeholders. Early artifacts create awareness, demos establish feasibility, and workshops generate ownership through participation.

Organizations that adopt this approach move faster with greater confidence. Decisions feel earned rather than forced, and approvals become confirmation moments rather than debate forums.

How can technology leaders translate technical value into executive relevance?

Technical accuracy alone rarely drives executive decisions. Leaders must translate system capabilities into the financial, operational, and strategic language each stakeholder uses to evaluate risk and return.

Finance leaders assess capital efficiency and downside exposure. Operations leaders focus on stability and implementation burden. Executives evaluate strategic positioning and organizational readiness.

Effective translation adapts framing without diluting substance. It connects performance improvements to outcomes leaders are accountable for delivering.

Technology leaders who master this translation layer advance faster and face less resistance. They are seen not as solution advocates, but as enterprise leaders who understand how change actually lands.

What distinguishes technology leaders who consistently secure buy-in?

Leaders who secure buy-in repeatedly treat influence as a compounding capability. Each initiative strengthens relationships, clarifies decision patterns, and expands internal credibility.

They document stakeholder preferences, learn from past objections, and cultivate champions who advocate beyond formal structures. Over time, approvals accelerate because trust already exists.

This advantage is structural, not charismatic. It is built through disciplined preparation, follow-through, and post-launch engagement.

Organizations benefit disproportionately from these leaders. Their initiatives ship more often, scale faster, and convert strategy into execution with less friction.